Sinking Funds Guide: Stop Getting Blindsided by Bills

You don’t have a “budgeting problem.” You have an ambush problem.

Because the bills that “come out of nowhere” are usually the bills that show up every year, like a needy ex with impeccable timing.

Car registration. Holiday gifts. Annual insurance. Back-to-school. The one dentist visit that costs as much as a small wedding. None of this is a surprise. It’s just… not monthly. And your monthly budget is out here acting like the calendar ends on the 30th.

Here’s the part nobody talks about: Most financial “emergencies” are just predictable expenses you didn’t pre-pay.

And when you don’t pre-pay them, you pay for them twice: once in stress, then again in credit card interest.

What sinking funds are (and why they feel like cheating)

A sinking fund is money you set aside little by little for a planned expense that hits later.

Think of it like turning a $600 annual bill into a boring $50 monthly line item. Boring is good. Boring is rich.

Sinking funds vs emergency funds (stop mixing these up)

People love to call everything an emergency because it feels dramatic. Your budget does not need a Marvel Cinematic Universe.

- Emergency fund: for true curveballs (job loss, urgent medical, “my car is making a sound that belongs in a horror movie”).

- Sinking funds: for expenses you know are coming (insurance premiums, holiday spending, car maintenance, annual subscriptions, travel, property taxes).

If you use your emergency fund for planned expenses, it stops being an emergency fund and becomes a “vibes fund.” Not recommended.

Why this matters right now (data, but make it painful)

According to a 2023 report cited by CNBC, about 60% of Americans are living paycheck to paycheck, and 70% are stressed about finances. Only 45% said they have emergency savings, and 61% report being in credit card debt.

Source: CNBC coverage of paycheck-to-paycheck and savings data

Sinking funds don’t magically fix income problems, but they remove the “surprise bill” excuse that keeps people stuck in the monthly panic loop.

Quotable truth: If it happens every year, it’s not an emergency. It’s your budget gaslighting you.

The psychology: why sinking funds work when “just be disciplined” doesn’t

Sinking funds win because they use two forces that are basically undefeated:

- Automation: willpower is a scarce resource and yours is being spent on notifications, snacks, and existential dread.

- Mental accounting: humans are wired to treat labeled money differently. “Vacation” money doesn’t get spent on DoorDash as easily as “extra cash.”

Meet Maya.

Maya is responsible. Has a 401(k). Uses her credit card for points. Says things like “we’re trying to be more intentional.”

Then December hits.

Gifts. Travel. Hosting. Random “holiday outfits” that apparently cost more than an index fund.

Maya didn’t overspend because she’s bad with money. Maya overspent because she budgeted like December was hypothetical.

A sinking fund turns December into… math. Not vibes.

What to use sinking funds for (aka: the bills that love jump scares)

Sinking funds aren’t just for Type-A spreadsheet monks. They’re for anyone who has ever said:

“I forgot my car insurance was due.”

Sure you did.

Here are the most common sinking funds, organized by the kind of chaos they prevent.

| Sinking fund | What it covers | Typical timing | Why it matters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Car maintenance | Tires, oil, brakes, repairs | Ongoing | Prevents “I guess I’m financing tires” moments |

| Auto insurance | Premiums, deductibles | Semi-annual or annual | Stops a predictable bill from wrecking a month |

| Home maintenance | Repairs, appliances, HVAC service | Ongoing | Homes are beautiful money pits |

| Medical | Copays, prescriptions, dentist/vision | Ongoing | Health expenses rarely stay polite |

| Holidays + gifts | Gifts, travel, hosting, donations | Seasonal | December is not a surprise; it’s a deadline |

| Travel | Flights, hotels, car rental, spending | Planned | Keeps vacations from becoming debt souvenirs |

| Annual subscriptions | Prime, iCloud, apps, memberships | Annual | Subscriptions are silent assassins |

| Taxes (freelancers) | Estimated taxes | Quarterly | Avoids the “April panic” and penalties |

| Kids expenses | Camps, activities, school fees | Seasonal | Kids have hobbies, and hobbies have invoices |

| Tech replacement | Phones, laptops, upgrades | Every 2 to 5 years | Your laptop will die at the worst time |

If you want your category system to stay clean while you do this, you’ll love a structured setup like FIYR’s approach in Budgeting Categories List: A Clean Setup That Works.

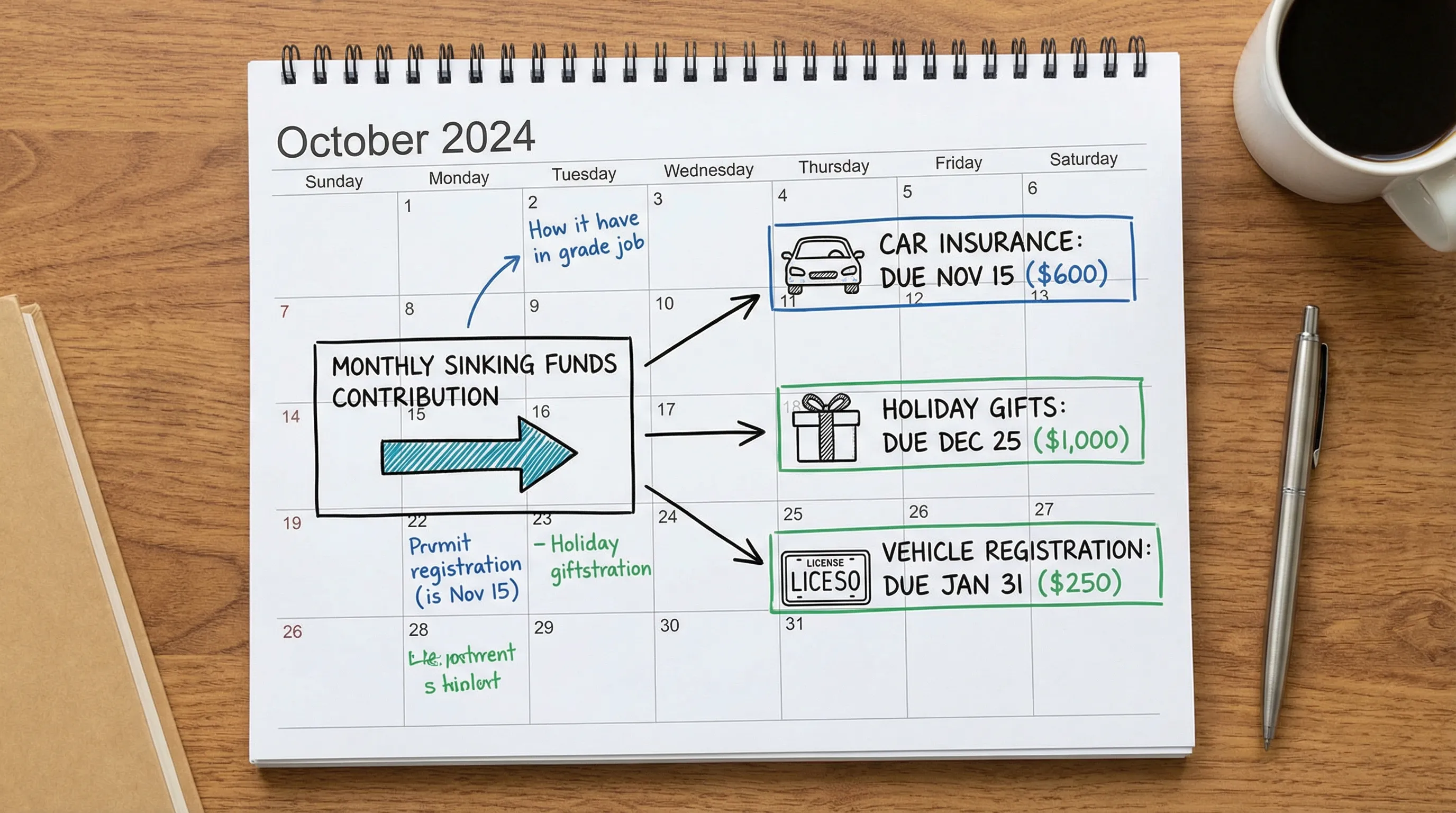

The math: how much to put in each sinking fund (no, you don’t need a spreadsheet)

Here’s the formula that runs the whole show:

Monthly sinking fund contribution = Target amount ÷ Months until you need itThat’s it. That’s the sorcery.

Example: turning “random bills” into monthly line items

Let’s say you’ve got these expenses coming:

| Expense | Amount | Due in | Monthly contribution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Car insurance | $600 | 6 months | $100 |

| Holiday spending | $1,200 | 10 months | $120 |

| Annual subscriptions | $240 | 12 months | $20 |

| Car maintenance | $900 | 12 months | $75 |

Total: $315/month

And yes, $315/month feels like a lot.

But it’s not “new spending.” It’s honesty. You were already spending this money. You just weren’t admitting it until it punched you in the face.

Quotable truth: Sinking funds don’t create expenses, they reveal them.

How to estimate amounts if you don’t know your numbers yet

If you’re coming from Mint (RIP) or you’re tired of apps that give you pretty charts and zero clarity, this is where tracking matters.

Use one of these:

- Last year’s totals (best)

- The last 3 to 6 months, annualized (good)

- A conservative placeholder you can refine (fine, just don’t make it fantasy)

If you need a quick way to stop guessing, start with a month of clean tracking and categorize ruthlessly. FIYR is built for this, especially with custom categories, category groups, and transaction rules that keep your data from turning into spaghetti.

Where to keep sinking fund money (so you don’t “accidentally” spend it)

There are two sane approaches:

Option 1: Keep the cash in one savings account, track the buckets in your budget

This is the minimalist approach. One pile of money, multiple “virtual” sinking funds tracked via categories/goals.

- Pros: simple banking setup, easy transfers

- Cons: requires you to trust your tracking system (and not your feelings)

Option 2: Use a separate savings account (or multiple buckets) for sinking funds

Some banks let you create buckets. Or you can use separate accounts.

- Pros: harder to raid, psychologically clean

- Cons: more accounts to manage, more transfers

Either way, the key is consistency: if you spend it, you categorize it against the sinking fund. Not “misc.” Not “oops.” Not “I’ll fix it later.”

If you want a budgeting system that can bend without breaking, sinking funds fit perfectly inside a layered setup like Flexible Budgeting: Build a System That Bends.

The setup: build your sinking funds in 45 minutes

You do not need a weekend retreat or a new journal.

You need a list, a few decisions, and one brave moment of realism.

Step 1: Make your “Bills That Blindside Me” list

Scan the next 12 months. Add anything that is:

- Annual or semi-annual

- Quarterly

- Seasonal

- Bigger than your typical weekly wiggle room

Examples: insurance premiums, car registration, memberships, travel, gifts, school costs, property taxes.

Step 2: Pick your starter sinking funds (start small, win fast)

If you’re new, choose 3 to 5 sinking funds.

My bias (because it works):

- Car maintenance

- Holidays + gifts

- Annual subscriptions

- Medical

- Travel

You can always add more once your system stops leaking.

Step 3: Set targets and due dates

For each sinking fund:

- Target amount

- Due date (or “ongoing” with an annual target)

- Monthly contribution

Step 4: Automate the transfer (or automate the tracking)

Automation is the difference between “I should” and “I did.”

You can automate in a couple ways:

- Auto-transfer to savings on payday

- Auto-allocate inside your budget categories

With FIYR, you can keep this clean using custom categories, goal tracking, and a safe-to-spend view so you know what’s actually available after you fund the future.

Step 5: Spend from the sinking fund category, not from hope

When the bill hits, categorize it to the sinking fund.

That’s the whole point: the expense lands, the system absorbs it, your month does not combust.

Quotable truth: The goal is not to predict every expense. The goal is to stop pretending you won’t have any.

Common sinking fund mistakes (so you don’t reinvent chaos)

Mistake 1: Creating 27 sinking funds on Day 1

Congrats, you just built a second job.

Start with the biggest pain points, then expand.

Mistake 2: Underfunding because you’re “optimistic”

Optimism is cute. Bills are not.

If you consistently miss the target, increase the contribution or reduce the plan.

Mistake 3: Raiding sinking funds for random spending

This is how sinking funds turn into a sad fiction novel.

If you keep raiding them, your budget needs a better Flex buffer or tighter category caps. The guardrails matter.

Mistake 4: Forgetting subscription creep

Annual renewals are the sneakiest kind of sinking fund trigger because you won’t notice until it’s too late.

Do a quarterly subscription audit, or at least track recurring charges so the “$119.99 who is she?” moments stop.

Related: Best Apps to Manage Subscription Renewals

Sinking funds with irregular income (freelancers, creators, small business owners, welcome)

If your income looks like a crypto chart, sinking funds are not optional. They are your stabilizers.

Here’s a simple approach that works even when your paychecks don’t:

Use a baseline month, then fund sinking funds like they’re payroll taxes

- Choose a baseline income you can usually hit (conservative, not delusional)

- Build your monthly budget off that

- Fund sinking funds first, then lifestyle

If you have high and low months, you can also fund sinking funds as a percentage of income, for example:

- 5% to car and home maintenance

- 5% to taxes (or more, depending on your situation)

- 3% to travel

- 2% to gifts

Then, in big months, you “catch up” and build buffer.

If you want the full system for variable pay, pair sinking funds with income smoothing from Budgeting With Irregular Income: A Practical System That Actually Works.

Quotable truth: Irregular income doesn’t break budgets, pretending it’s regular does.

The FIRE angle: sinking funds protect your savings rate

If you’re chasing FIRE, your savings rate is the engine. Surprise bills are sand in the gears.

Without sinking funds, people do this:

- Surprise bill hits

- Credit card covers it

- Next month’s cash goes to paying the card

- Savings rate drops

- Timeline to FI quietly stretches

Also, credit card interest is not a “small fee.” It’s a wealth tax.

The average interest rate on credit card plans has been above 20% in recent years.

Source: FRED: Commercial Bank Interest Rate on Credit Card Plans

Sinking funds help you keep your savings rate steady, which matters a lot more than squeezing an extra 0.3% out of your portfolio.

If you want the macro view, pair this with Savings Rate for FIRE: The Fastest Path to Freedom.

A simple sinking funds “cheat sheet” you can copy

If you want a clean starter template, use this list and adjust amounts as you learn your real numbers:

- Car maintenance: ongoing, annual target

- Medical: ongoing, annual target

- Annual subscriptions: annual target, due month(s)

- Holidays + gifts: due December

- Travel: due month of trip

- Home maintenance (if applicable): ongoing, annual target

- Taxes (if applicable): quarterly

And here’s the rule that keeps it from getting messy:

If it’s predictable and not monthly, it belongs in a sinking fund.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is a sinking fund in budgeting? A sinking fund is money you set aside gradually for a planned expense that happens later (like insurance, holidays, or car repairs), so it doesn’t wreck one month’s budget. How many sinking funds should I have? Start with 3 to 5 based on your biggest recurring pain points. Add more only after you can fund and track the first set consistently. Should sinking funds be in a separate bank account? They can be, but they don’t have to be. You can keep cash in one savings account and track sinking fund buckets inside your budget, as long as your tracking is consistent. Are sinking funds the same as an emergency fund? No. An emergency fund is for unexpected, urgent events. Sinking funds are for known expenses that happen irregularly. How do I calculate sinking fund contributions? Use this formula: target amount ÷ months until due. Example: $600 due in 6 months means $100 per month.Stop getting blindsided, start getting boring (boring is the goal)

Sinking funds are not fancy. They are not aesthetic. They will not go viral on TikTok.

They are, however, the difference between:

- “Why is everything so expensive?”

and

- “Yeah, that bill was already handled.”

If you want an easier way to run sinking funds without turning your budget into a spreadsheet graveyard, FIYR helps you keep everything organized with custom categories, automatic transaction rules, goal tracking, subscription tracking, and a clear safe-to-spend view.

Explore the FIYR blog for more systems that actually work at blog.fiyr.app, and when you’re ready, set up your categories once, then let the rules do the boring work for you.