How to Calculate FIRE Number (Without Guesswork)

Most people treat their FIRE number like it’s a sacred prophecy.

It’s not.

It’s a math problem sitting on top of messy human behavior, subscription creep, healthcare roulette, and an economy that keeps inventing new ways to charge you $19.99/month for “premium.”

And here’s the uncomfortable truth: you don’t need a better calculator, you need better inputs.

Because if your spending data is wrong (or vibes-based), your FIRE number is just a well-formatted lie.

The no-guesswork FIRE number formula (the one you’ll actually use)

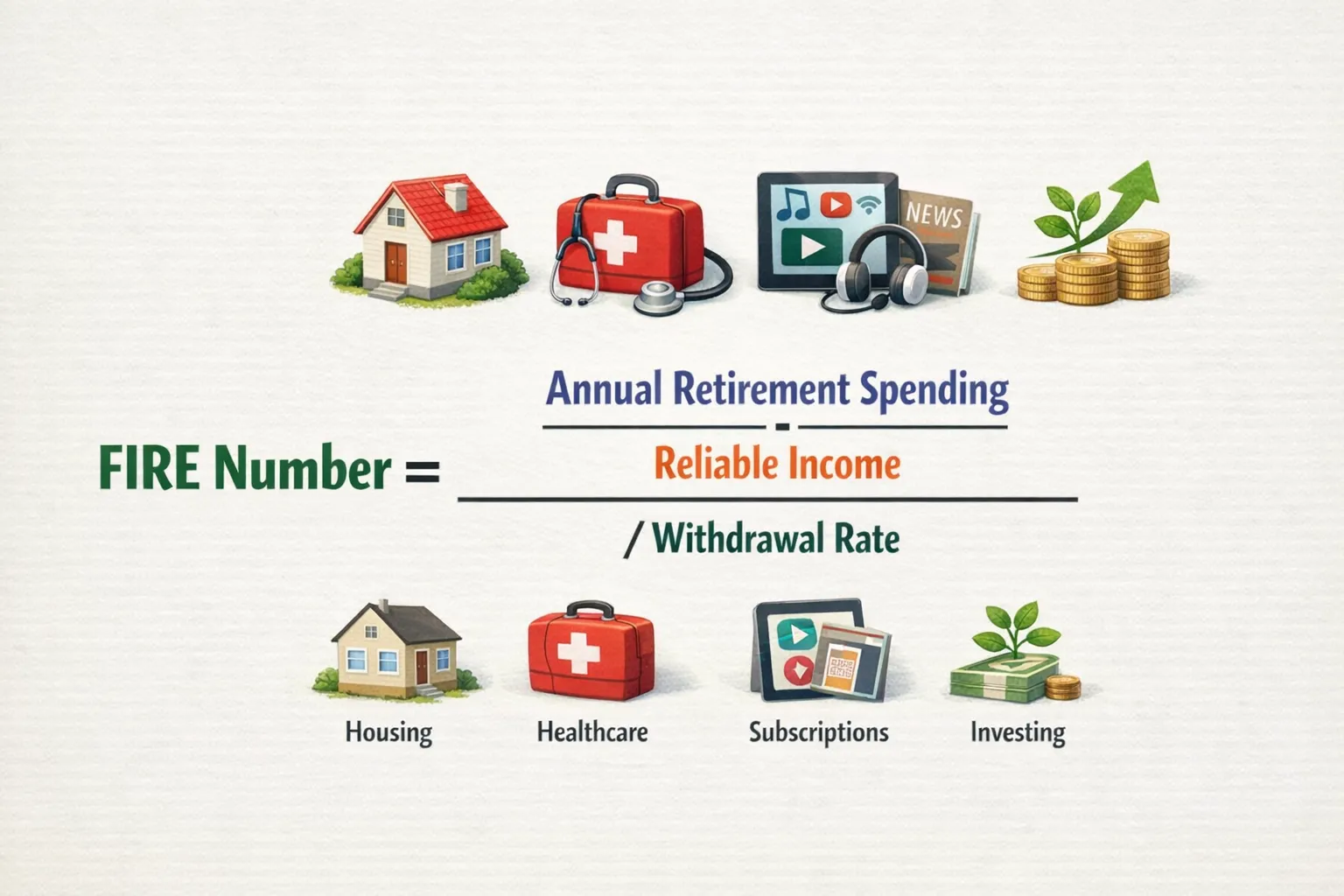

At its simplest, the FIRE math is clean:

FIRE number = annual spending in retirement ÷ safe withdrawal rateMost people start with the classic:

- 4% rule (roughly the “Rule of 25”) → multiply spending by 25

- More conservative: 3.5% (multiply by ~28.6)

- Even more conservative: 3% (multiply by 33.3)

But “annual spending in retirement” is where everyone faceplants.

Meet Jake.

Jake told me he spends “about $4,000/month.” Which is a very adult sentence that means, “I have not looked at my transactions since the Obama administration.” When he finally pulled 12 months of data, his real spending was $5,450/month.

That difference is not cute.

At a 4% withdrawal rate:

- $4,000/month ($48,000/year) → $1.2M

- $5,450/month ($65,400/year) → $1.635M

Same person. Same life. Different spreadsheet honesty.

Your FIRE number isn’t hard. Your data is.

Step 1: Calculate your real annual spending (not your “budgeted” spending)

If you want to know how to calculate your FIRE number without guesswork, you need a baseline that doesn’t rely on memory.

Use the “Last 12 Months, Real Life” method

Pull your last 12 months of transactions and compute:

Annual spending baseline = total outflows minus transfers and debt principal shufflesThis matters because personal finance apps, spreadsheets, and even smart people routinely commit the same sins:

- Counting credit card payments as “spending” (double counting)

- Letting Amazon become a category (Amazon is not a category, it’s a lifestyle)

- Treating Venmo/Zelle like an expense when it’s really splitting rent

This is why clean categorization is not a nerdy detail. It’s the foundation of your retirement math.

If you’re using FIYR, this is where it shines as a modern alternative to Mint, Monarch Money, Copilot, Rocket Money, and Quicken: income and expense tracking, customizable categories, automatic transaction rules, and subscription tracking keep your baseline from turning into a fiction novel.

What to include in “spending”

Count what you actually spend to live your life (and enjoy it), including:

- Housing (rent or mortgage interest, taxes, insurance, repairs)

- Utilities, phone, internet

- Groceries, dining, coffee you swear is “social”

- Transportation (car payments, gas, insurance, maintenance, rideshare)

- Healthcare costs you pay today (premiums, copays, prescriptions)

- Childcare and kid-related spending

- Travel and hobbies

- Subscriptions (yes, all 37 of them)

And then things get interesting.

Convert irregular and annual costs into monthly reality

Most people underestimate spending because big costs hide in the bushes.

Examples:

- Insurance paid semi-annually

- Property taxes

- Holiday spending

- Annual subscriptions

- Travel spikes

The fix is simple:

Annualized spending = (total last 12 months spending) + (known upcoming annual costs not captured) - (one-time anomalies you won’t repeat)Don’t overthink “one-time anomalies.” If you had a surprise $4,000 car repair, it’s not a one-time anomaly. It’s a recurring event with an inconsistent schedule.

Quotable truth: Your budget isn’t monthly. Your life is lumpy.

Step 2: Decide what “retirement spending” means for you (future-you is expensive)

Your current spending is a starting point, not a verdict.

Retirement spending usually changes because:

- Some costs drop (commuting, payroll taxes, saving for retirement because you’re… in it)

- Some costs rise (healthcare, travel, hobbies, “it’s Tuesday so we’re at brunch”)

Here’s a clean way to handle it:

Retirement spending estimate = current annual spending + adds - subtractsThe biggest “adds” people forget

- Healthcare: If you retire before Medicare, this can be a major line item

- Taxes: Retirement withdrawals are not magically tax-free (unless you built a tax-free strategy)

- More time, more spending: Free time is either cheap (library, hikes) or catastrophic (golf, boats, international “finding yourself” trips)

The biggest “subtracts” people assume incorrectly

- Mortgage payoff: Great if it’s real and timed, not a dream

- Kids leaving: Sometimes they “leave,” then return with laundry

- Work costs: Commute, lunches, wardrobe, convenience spending

If you want a practical shortcut, build two versions:

- Baseline FIRE: your “normal life, but not working” number

- Fun FIRE: baseline plus the stuff you’ve been postponing

Because “I’ll just travel more” is not a plan. It’s a budget line.

Step 3: Pick a withdrawal rate (this is where the internet starts yelling)

The 4% rule comes from historical backtesting of stock and bond portfolios, popularized by research like the Trinity Study. It’s a useful rule of thumb, not a divine guarantee.

Use a withdrawal rate that matches your risk tolerance and situation:

- 4%: common starting point for “standard” FIRE math

- 3.5%: more conservative, often used for longer retirements or extra caution

- 3%: very conservative, sometimes used when you want a wider margin (or sleep like a baby)

Here’s what those rates do to your target.

| Annual spending | 4% rule (÷0.04) | 3.5% (÷0.035) | 3% (÷0.03) |

|---|---|---|---|

| $40,000 | $1,000,000 | $1,142,857 | $1,333,333 |

| $60,000 | $1,500,000 | $1,714,286 | $2,000,000 |

| $80,000 | $2,000,000 | $2,285,714 | $2,666,667 |

| $100,000 | $2,500,000 | $2,857,143 | $3,333,333 |

Notice what changed.

Not your lifestyle.

Not your job.

Just one assumption.

Quotable truth: A “small” percentage in retirement math is a six-figure mood swing.

Step 4: Subtract reliable income the right way (don’t double-count optimism)

If you’ll have income in retirement that is truly reliable (pension, Social Security later, annuity income, rental income you trust), you can subtract it from your spending need.

Use this version:

FIRE number = (annual spending in retirement - reliable annual income) ÷ withdrawal rateExample:

- Retirement spending target: $84,000/year

- Reliable income: $24,000/year (pension, or later Social Security)

- Withdrawal rate: 4%

FIRE number = ($84,000 - $24,000) ÷ 0.04 = $60,000 ÷ 0.04 = $1.5M

Two important notes:

- Only subtract income you’d bet your house on. If it’s “probably” income, keep it out until it’s real.

- If income starts later (like Social Security), treat it as a phase shift: you may need a bigger portfolio bridge until it kicks in.

Here’s the part nobody talks about: timing matters more than totals.

Step 5: Add guardrails (because life loves plot twists)

You can do the math perfectly and still get wrecked by reality.

Not because you’re dumb, but because modern finances are stressful by default.

CNBC reported that 60% of Americans are living paycheck to paycheck, and financial stress is widespread, with many households lacking meaningful emergency savings and carrying credit card debt (CNBC coverage). Translation: even high earners can be one bad month away from chaos.

So you build guardrails.

Three guardrails that reduce FIRE-number delusion

1) The “boring buffer”Add a cushion to your spending estimate (often 5% to 15%). Not because you’re bad at math, but because you’re human.

2) The “one-time costs” fundSeparate from your FIRE number, set aside cash for lumpy stuff: car replacement, home repairs, medical deductibles, helping family. This keeps your withdrawal plan from getting ambushed.

3) The “subscription and leakage audit”Tiny leaks add up to big retirement math.

If you track subscriptions and recurring charges in FIYR, you get a cleaner view of what’s truly fixed versus what’s optional. And optional spending is the easiest lever in the early retirement game.

Quotable truth: The goal is not perfection, it’s resilience.

Step 6: Do a 10-minute sensitivity test (aka stop pretending your assumptions are facts)

A no-guesswork FIRE number is not one number. It’s a range.

Run three scenarios:

- Base case: your best estimate of retirement spending, 4% withdrawal

- Conservative: spending +10%, 3.5% withdrawal

- “Life happens”: spending +15% and a few years of ugly markets (this is about psychology as much as math)

You’re not trying to predict the future. You’re trying to prove you can survive it.

This is where tracking tools matter. If your spending categories are clean, your net worth is accurate, and your savings rate is tracked consistently, scenario planning goes from stressful to straightforward.

FIYR’s FIRE-focused insights (including a FIRE date calculator driven by your real data) make this less like tarot and more like operations.

A realistic example: calculating a FIRE number from scratch

Let’s do the full workflow with a fictional person who is painfully real.

Meet Priya. She’s 34, a former Mint user, and she’s tired of budgeting apps that act like “Dining Out” is a moral failure.

After 12 months of clean tracking, Priya’s numbers look like this:

- Total annual spending: $72,000

- She expects retirement will be slightly more expensive (healthcare plus more travel): + $8,000

- She plans to drop commuting and work extras: - $3,000

Retirement spending estimate = $72,000 + $8,000 - $3,000 = $77,000

She wants a bit more safety, so she chooses 3.5%.

FIRE number = $77,000 ÷ 0.035 = $2.2M (rounded)

Now the twist: she expects some later retirement income.

At age 67, she estimates Social Security might cover $18,000/year. She does not subtract it yet because:

- She’s retiring early

- The timing matters

- She’d rather be pleasantly surprised than financially cornered

So she keeps $2.2M as her working target and treats Social Security as upside later.

Quotable truth: Optimism is not an asset class.

The biggest mistakes people make when calculating their FIRE number

Most FIRE-number errors are not math errors. They’re lifestyle and data errors.

Mistake 1: Using a “good month” as the baseline

If you calculate spending from a month where you cooked at home, didn’t travel, and felt morally superior, congratulations. You have measured a fantasy.

Use 12 months.

Mistake 2: Ignoring subscription creep

You cancel one streaming service, then immediately sign up for another because the algorithm suggested a show where British people bake aggressively.

Subscription visibility matters because recurring costs multiply directly into your FIRE number.

Example: cut $100/month.

That’s $1,200/year.

At 4%, your FIRE number drops by $30,000.

Not life-changing, but also not nothing.

Mistake 3: Treating debt and spending as separate planets

High-interest debt increases your required cash flow. Period.

Your FIRE plan should include whether debt will be gone before you retire, and what your spending looks like with and without it.

Mistake 4: Forgetting that taxes exist

If you’re withdrawing from pre-tax accounts, a chunk goes to taxes. How big depends on your mix of account types and filing situation.

You don’t need to be a tax wizard to account for it. You just need to stop assuming 0%.

Turning your FIRE number into a plan (so it stops being a vibe)

A FIRE number is only useful if it changes what you do on Tuesday.

Here’s the simplest execution loop:

1) Track the three metrics that actually move the needle

- Annualized spending (rolling 12 months)

- Savings rate (because it controls your timeline)

- Net worth (because it’s the score, not your credit limit)

FIYR is built for exactly this kind of loop: spending tracker, income and expense charts, net worth tracking across assets and liabilities, savings rate calculation, and goal tracking with a “safe-to-spend” view.

2) Create one label that exposes your biggest leak

Pick a label like “Eating Out,” “Kids Stuff,” “New York Trip 2025,” or “Oops.” Then tag transactions for 30 days.

The goal is not shame. The goal is signal.

When you can see a spending pattern clearly, you can decide if it’s worth working longer for.

Quotable truth: Clarity is what turns sacrifice into choice.

3) Use one income lever if you’re stuck

Yes, cutting spending matters, but at some point you run out of things to cut without making life sad.

If income growth is your lever (side hustle, freelance, business), you need prospects.

One surprisingly effective approach is to find where people are already complaining about the problem you solve, then show up with something helpful. That’s basically Reddit in a trench coat.

If you’re building a business and want a more automated way to discover relevant threads and engage authentically, tools like Redditor AI can help you turn Reddit conversations into customers. More income means a higher savings rate, and that is the closest thing to a cheat code in FIRE.

A quick “without guesswork” checklist you can reuse every year

Recalculate annually (or anytime life changes), using the same inputs and rules:

- Pull last 12 months spending, fix categorization errors, remove transfers

- Monthly-ize annual expenses and include irregular big costs

- Adjust for retirement adds/subtracts (healthcare, taxes, commuting changes)

- Choose withdrawal rate (4%, 3.5%, or 3% based on your risk tolerance)

- Subtract only truly reliable income, and respect timing

- Run a 3-scenario range, not a single number

If you do this once, your FIRE number stops being a scary mystery and becomes what it should have been all along: a dashboard gauge.

Because the actual flex is not retiring early.

The actual flex is waking up one day and realizing money no longer gets to bully you.

Quotable ending: Your FIRE number isn’t a finish line, it’s a boundary. Cross it, and your life gets bigger.